Around 1900, Catherine Marshall Gardiner of Laurel, Mississippi, read an article about Native American baskets and found herself tempted by the possibility of collecting them. At first, she planned to collect only contemporary baskets, but, she said, “the lure of old and fine work specimens soon gained the ascendancy.” Mrs. Gardiner’s quest for fine specimens led her to contact basket dealers, other collectors, officials and teachers on reservations, and weavers, eventually becoming part of a national network of other basket aficionados. By 1923, when she donated her collection of almost 500 baskets to the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, she had amassed one of the most representative collections of North American Native basketry in the Southeastern United States. In the intervening decades, the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art has added to the collection, particularly with baskets from the Southeast, but Mrs. Gardiner ’s vision has remained the foundation of the collection.

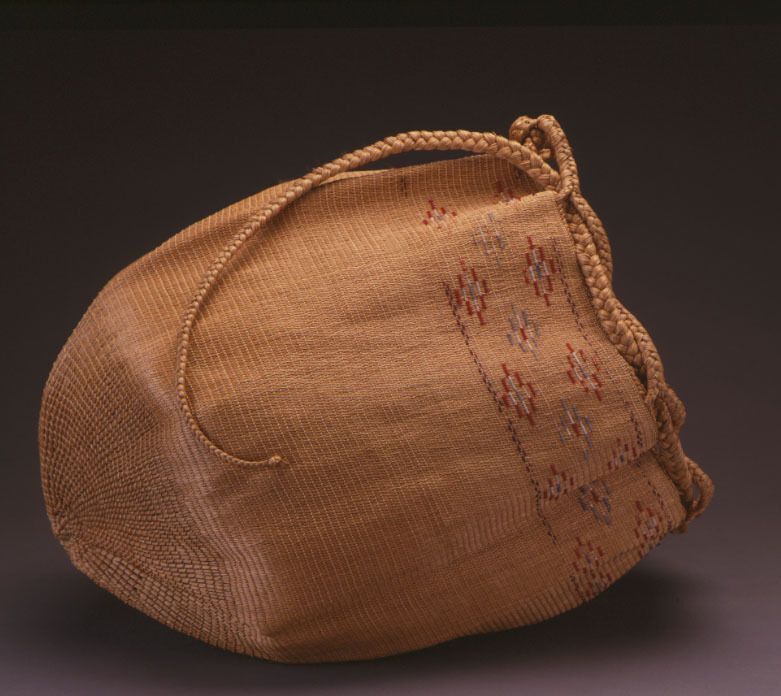

Basketry is an infinitely variable medium; baskets can be simple, unadorned objects or objects of great complexity. Yet even the most practical basket, well made, can be a thing of beauty wherein form follows function, centuries of tradition influence the weaver, and the materials reflect the land in which the artist is grounded. Basketry began as a utilitarian medium, developed to produce tools for cooking, storage, clothing and all aspects of domestic life. A painted and tasseled burden basket (c. 1870) that was produced by a San Carlos Apache basket weaver shows elaborate ornamentation on an everyday utilitarian object. A fish bag (before 1903) features a drawstring of thickly braided grass. The Algonquin’s makak form, made from birch bark, is a maple sugar container (c. 1976).

Fancy baskets, often highly decorated, were made for trade or for gift giving. An Eastern Pomo feathered plague (before 1903) is decorated with brilliantly colored feathers from four different birds. Basketry has also been used as a sculptural medium; woven effigies of humans and animals are found in many basketry traditions. Coushatta basket weavers such as Edna Langley have developed a thriving new tradition of effigy baskets in the form of chickens and other animals made from longleaf pine needles.

Baskets are used in dances and in other kinds of sacred ceremonies and rituals. Yoruk Male dancers formed a line and held the Jump Dance basket (before 1915) in their right hands, swinging it rhythmically up, down, and forward. A large Pima bowl (c. 1900), which exhibits the vortex pattern, was probably turned upside down to use as a resonator for a musical instrument during the Rain Feast. Haida chiefs wore painted woven hats on very ceremonial occasions.

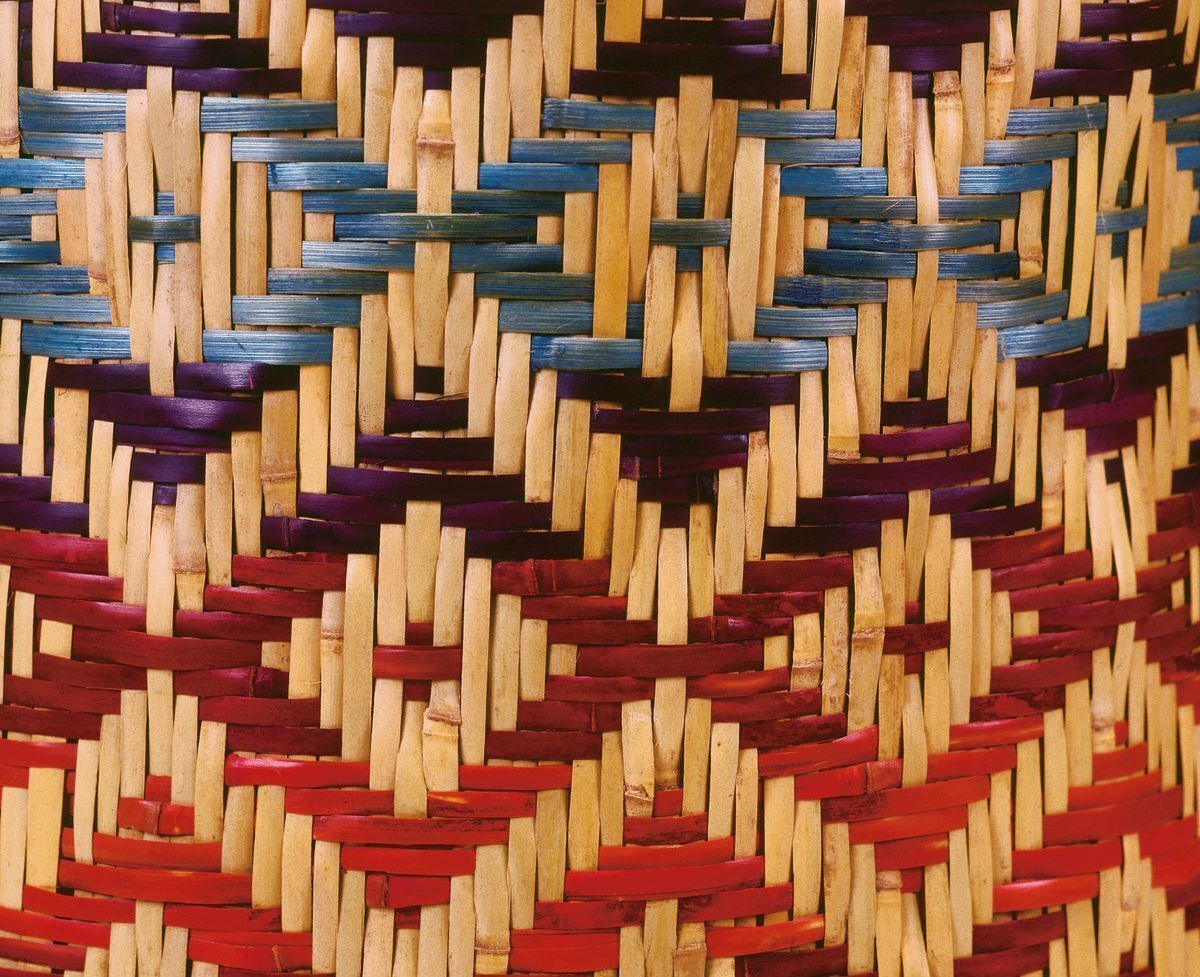

Although Native American basketry traditions suffered in the dislocations and epidemics of the 18th and 19th centuries, many tribes are reviving the old techniques and encouraging the development of weaving skills in the community. Today’s Native American basket makers work within a tradition that is centuries old. For example, there are Choctaw weavers in Mississippi who are fifth generation basket weavers, following a tradition passed down from mother to daughter over many decades. Linda Farve, maker of the Museum’s enormous, brilliantly hued clothes hamper (1985), is a master weaver of contemporary Choctaw baskets.